Len Charney founded and built the BAC practice department for 20 years and built up a joint connection

In the 20 years in which Len Charney taught in the BAC and serving as a dean of practice, he never came to lessons and taught.

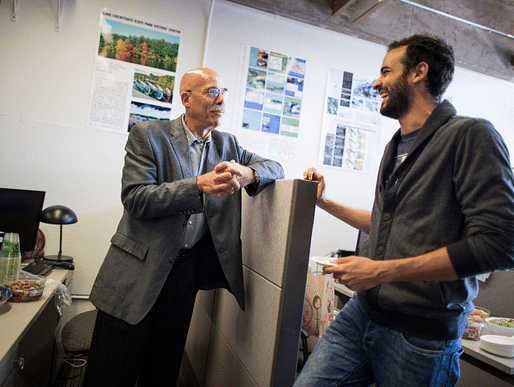

He always viewed his important role as the students to judge what they learned outside the classroom as an essential element of their BAC training. He enjoyed asking them direct questions and returning when they answered and started an individual path of self -discovery.

“They ask questions and then wait for the light bulbs to start in the heads of the students,” he said of his teaching philosophy. “What you teach should always be based on what the students want to learn.” He continued: “It is about trusting the students and supporting them when they get a clear feeling for what they need to know to surpass themselves and achieve their goals.”

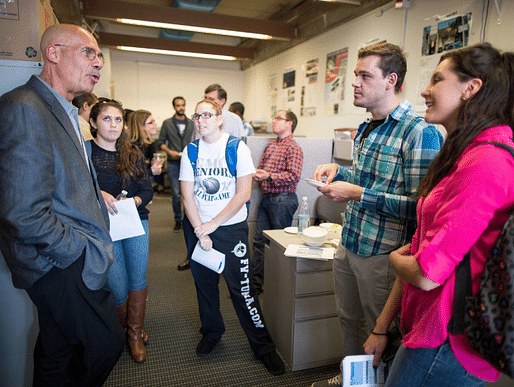

Today, on the second floor, BAC students in blazers shake potential employers and practice supervisory authorities at a career fair. Many of the companies and Boston-based organizations that have taken the time to meet and recruit themselves with students have been built up for the first time by len-the stone-soluble relationships between school, design professionals and the community of the community that have been continued to this day.

He waves some of them and then takes the elevator onto the third floor, where he pulls his black fingerless gloves, cuts from a coffee thermal capsule and thinks about his BAC chapter outside one of the offices in which he set up a business two decades ago.

When Len joined the BAC in 2004, the school was already deeply committed to its many years of conviction that the pupils were best learned by experimental education-an academic study with real world practice in supervised environments. At this point, the students submitted reports or drawings to the Faculty of Voluntary Practice, which generally approved the work without direct interaction. There were no formal systems that help the precautionary authorities and students to connect job experiences with learning in the classroom.

Len said: “The concept of an individual learning contract was good, but the evaluation process for learning programs required serious update.” He achieved exactly that with the support of the administration. The documentation of the work was strictly, and the students were expected to submit their progress in the personal personality for trained practical auditors every semester. Supporting criticism, mentoring and career networking everyone came into play.

“It was not about theoretical concepts that BAC students took their experiences away,” said Len. “The exercise prepared them for the workplace where they have deadlines, colleagues and schedules and are sometimes exposed to conflicts and resistance.”

In his own lives, Len always had his greatest moments of light bulb. He never wanted to become an architect or educator during the experience that “learning through philosophy”. While he studied the government in Cornell in the 1960s, he and a close-knit group of friends' etwas put their own “happy pranksters” in ithaca, New York Create collective collective in the forest. In this semester they built and lived in a provisional village with huts, yurts and even a secure train cabin that changed the theory into practice long before it became his job.

“From there,” said Len, “I permanently included in the colloquial language of art, design and community building. I also managed to write the only book about yurt building that was ever published.”

After graduation, he taught Woodshop on an alternative high school. John Dewey, the father of experimental education, deeply influenced him as an educator. “His philosophy was about social learning, critical thinking, solving real problems and civic responsibility.” Interestingly, len would bring these values to the BAC practice department decades later. First, however, he followed a master of teaching on Antioch College, followed by an architecture master on.

The next chapter of his career comprised design and building interventions that changed the lives of everyday New Englanders. His work ranged from the direction of design and construction and the construction of a non -profit organizational housing developers to project management for a company for health facilities and the establishment of companies and as a director for planning and development for the Cambridge Housing Authority.

When a future role with -peer who conducted the BAC search committee for LENS was convincing for the application, Len was so fascinated by the school's pedagogy that he jumped in without hesitation.

Len said about these early years and said: “The BAC was the only school in the United States with such a strict exercise environment at that time. We were the outlier. It was only in the last decade that the mainstream of design training started to listen and learn from what we have started since my predecessor, Don Brown, the practice department six decades ago.”

In 2006, Len developed and headed a multi-year scholarship for the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Practice Academy, through which the BAC worked with companies in the Boston region to investigate how corporate and architectural industry introduced the transformative new technology of building information modeling (BIM). When the economy collapsed in 2008 and many companies were unable to hire students, Len started the first version of the Gateway-to-Practice Initiative, a nationally recognized model in which teams of BAC students and intentions per bono planning, design and modest construction services offer more than 200 non-profit organizations, neighborhood associations and municipal care agencies.

To date, more than 2,000 BAC students have participated in the Gateway program and forgiven their skills to everyone, from the scouts to non -profit organizations that support shakes, government authorities who need master plans, or a garden club that requires a new toolshed.

Sarah Howard, MDS-SD'21, was once a doctoral thesis and viewed himself as a mentee. A BAC training was so crucial for Sarah's career that she now acts as Interims Vice President for Progress and Strategic Relations.

“They let us in as their mentees,” she said during our conversation. “It was not hierarchical. There were always two people who had a dialogue with a dialogue. They helped us together with what we had to learn, but they always gave us space in the sandpit to find out things in a way that made sense for us and made sense for us.”

Len nodded thoughtfully. It is so much about the mentoring students not to have a one-person prescribing solution. “It's about running and supporting quietly on the side,” he said.

Len never stopped learning and growing. He founded a Men -Memoir writing group that was supposed to publish their first anthology this spring: four old men who write together: 40 stories with grace and humor.

Len is inspired by American writers and poets. During our interview, he quoted Wendell Berry, who wrote about the need to lose himself and her own selfish needs instead of pursuing the typical modern search to “find himself” as an individual. “To lose yourself means to become part of something larger than becoming and becoming part of the community,” concluded Len.

Interestingly, Berry's name and philosophy also appeared when I spoke to Ed Toomey, who was the first provost of the BAC, about the work that he and Len achieved in close cooperation. Len Ed recently called and they spoke for hours about Berry's writing.

According to Ed, the growth and strengthening of the community was his colleague's life mission: “Len always kept an eye on what was taught and how it was learned. He was not only interested in the product, but also in the process,” said Ed. “Teaching and learning are a joint venture for a purpose – and this purpose for Len has a cultural effect.”

The full impact of LENS work in the BAC will continue to have a wavy effect in the coming decades.