By Sym Posey | The Birmingham Times

Most students are asked one question in elementary or middle school: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” – Jeremy Cutts remembers saying he “wasn’t really sure.” But that would soon change fundamentally.

“My dad was an electrical engineer, so maybe I thought so. But then someone said to me, 'Hey, man, you like drawing and you're good at math. Have you ever thought about being an architect?'”

Cutts said he looked at an architect's career and decided it was something he would enjoy and “the rest is history,” he told the Birmingham Times.

“I made the decision that I [was] “I’m going to try it and it turns out it’s something I love,” he added. “I was lucky in that respect.”

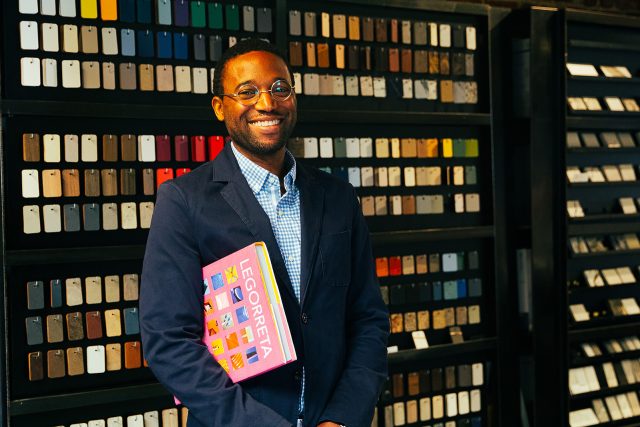

Cutts is a graduate of Auburn University and an associate at Williams Blackstock Architects, a Birmingham-based full-service architectural design firm with expertise in projects of varying size and scope. He has been with the company for 14 years.

His professional activities throughout Alabama include serving as project manager on several large projects – Lott Middle School in Citronelle; the historic Ramsay McCormack Building in Ensley; the Tuskegee Center for Genomics and Health Disparity Research at Tuskegee; and the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) Pavilion in Montgomery.

And for his work on these and several other projects, Cutts was named “Rising Star of the Year” by Multifamily Executive (MFE) magazine, a national award that recognizes an individual in the housing industry who has demonstrated vision, innovation and strong leadership skills while making significant contributions to their company, their community and the industry as a whole.

“The living laboratory”

One of the 38-year-old's goals is to spend time in Mexico studying a project called the Housing Laboratory, a small campus with 32 affordable housing prototypes in the city of Apan.

“The intent of the Housing Laboratory is to serve as a place where architects can visit their home country, study, and then apply the relevant aspects to affordable housing ideas,” Cutts said, adding that its focus is to reshape the future of multifamily housing, particularly affordable housing, through thoughtful, equity-focused design.

“At the heart of my ambitions is the desire to close the gap between rental housing and home ownership,” he said. “Design can give residents the opportunity to take pride in their homes and, over time, become stakeholders in their neighborhoods. The goal is to integrate pathways to ownership into future multifamily models and give residents the opportunity to directly benefit from the improvements and economic vibrancy of the communities they help shape.”

Love of giving back

Cutts grew up between Huntsville, Alabama, where he spent most of the year with his mother, Tammy Allen, and two younger sisters, and Atlanta, Georgia, where he spent summers with his father, Raymond Cutts Jr., an engineer.

While attending the now-closed Edwards H. White Middle School in Huntsville, young Cutts was required to write an essay about what he wanted to be when we grew up. “Becoming an architect really appealed to me,” said Cutts, whose educational path took him to Auburn University School of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape Architecture (APLA), where he graduated with a Bachelor of Architecture in 2010.

During his studies he developed a love for his craft and for giving back: “When I started, I recognized the opportunity [architecture] being able to impact people in communities in ways that I’ve always wanted to.”

“I started traveling a little bit more,” Cutts added. “I was in different rooms and learning about architecture and I realized that there are some really wonderful rooms, just the quality of space that I was never exposed to as a kid in the places that I grew up.”

These experiences led to volunteer positions with DesignAlabama, a nonprofit organization that helps local leaders imagine new forms of housing to improve community design and quality of life in Alabama. His work with DesignAlabama allowed him to work in smaller cities across the state, giving him personal insight into the need for compassionate solutions to affordable housing.

One of his most memorable projects was working on the Equal Justice Initiative pavilion in Montgomery, Cutts said.

“Being aware of it [EJI Executive Director] “Brian Stevenson and all the work that he and his group do, I can't really express the appreciation I have for it,” he said.

The EJI is an Alabama-based nonprofit organization that advocates for racial and economic justice by providing legal representation to those wrongfully convicted or sentenced, challenging the death penalty, and assisting people released from prison with reintegration.

“The opportunity to make even a small contribution to the work and mission of EJI is something that will stay with me forever,” said Cutts, who currently lives in Birmingham with his wife, Sierra, and his two sons, Justice, 8, and Judah, 5, with whom he enjoys making music. The family owns several instruments, including a keyboard, drums and guitars, but “my kids have really gotten used to it.” [artificial intelligence (AI) tools] to make music,” Cutts said.

“First they will beatbox, [imitate the sounds of a drum machine using the voice]or hum a melody, then we can load that into an AI generator that creates a whole track.”

The 2 percent

Cutts is part of a small group in a specialty area – African American architects. The National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB), a nonprofit organization that helps set state guidelines for examinations and licensing, reported that there were 121,603 licensed architects working in the United States in 2023. The proportion of Black or African American architects has changed slightly over the past five years, with Black architects making up just 2 percent of practitioners.

“I’m proud to be part of this small group, but I also feel a responsibility to help increase this percentage,” Cutts said. “I think, being aware of the fact that there aren’t many black architects, I do my best to live up to that truth.”

Of his chosen profession, he added: “Most people don't know what architects do, and even fewer know that architects care. … What I've learned over time is that when it comes to the community, and particularly Black people, [many] one of the landmarks we care about… like the 16th Street Baptist Church [were designed by Black architects].”

The historic house of worship, founded in 1873 as the First Colored Baptist Church of Birmingham, Alabama, was the first black church in Birmingham. In 1880, the congregation moved to its current location at 16th Street and 6th Avenue North and Wallace Rayfield, Alabama's only black architect, was hired to design the new church building.

One of Cutts' career goals is to make high-quality design accessible to people in places often inaccessible to typical architects.

“There are different levels of quality in design, and the quality of the space can have a real impact on a person’s quality of life,” he said. “That's what really drives me when it comes to reaching out to communities where often a lot of people don't have the same capacity. Whether it's volunteer work… or just going into these communities, you get to know people who have needs. I just have the skills and passion to be able to help in those situations.”